Beautiful design verses housing numbers

Which matters more, beauty or meeting housing targets? It’s a decision hanging in the balance in many appeals. While decision makers are entitled to come to their own view, it can be instructive to look at Secretary of State decisions to gauge the current mood.

We know the Government put great store on housing delivery. On the other hand, the July 2021 revisions to the NPPF put the emphasis on beauty. For many schemes, higher housing numbers and more affordable housing are at the expense of slightly less public open space, a generally heavier urban form and fewer grand architectural flourishes. So where does the balance lie?

In a recent recovered appeal (APP/Q1445/W/20/3259653) at Brighton Marina, the Inspector acknowledged the Secretary of State might come to a different balance. He noted the proposed development met Local Plan policies expecting high densities of a minimum of 100 dwellings per hectare. On the other hand it was arguably contrary to Local Plan policies on design and to NPPF paragraphs 130 & 134.

While the Inspector ultimately prioritised design over delivery and recommended dismissing the appeal, he recognised the Secretary of State could justifiably reach the opposite decision. He concluded, “that while I attach weight in the way I have set out, the Secretary of State might, perfectly reasonably, do so differently and conclude the opposite in terms of accord with the development plan read as a whole.” Quite. The flexibility of the English discretionary planning system in a nutshell.

This case at Brighton waterfront is interesting because the Secretary of State decided to endorse his Inspector’s decision and prioritise ‘beauty’ over housing delivery. It also provides a valuable comparison between the existing approved scheme and the dismissed design, showcasing some design principles which can be applied to smaller schemes facing similar dilemmas.

The fallback excuse

The Inspector acknowledged that his get out of jail card (although he didn't call it that) might normally be that, “a better designed scheme could bring forward the same or largely the same benefits”. Therefore dismissing the appeal could lead to a better design that delivers both housing numbers and beauty. This familiar reasoning is so often used by Councils and Inspectors, to the frustration of applicants and appellants.

To his credit, the Inspector recognised that relying on a future scheme would lead to delay and would therefore worsen the housing delivery problem. Neither could the extant consent be used as an excuse as it would deliver less housing overall. One way or another, dismissing the appeal would materially harm housing delivery. He therefore professionally tackled the thorny issues of, ‘What is good design?’ and ‘When does design trump housing delivery?’

Alternative designs with lower densities

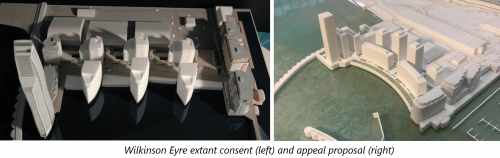

NPPF paragraph 124 supports higher densities and the proposed development met those aspirations, providing 1,000 dwellings and over 1500sqm of commercial spaces. It was significantly more efficient in its use of land than the extant consent known as ‘Wilkinson Eyre’ that could deliver 658 homes, if it was ever fully built out (BH2006/01124).

The Inspector noted the appeal scheme was in accordance with the Local Plan Inspector’s findings that the marina should make as significant a contribution as possible to the housing needs of the area, given a significant shortfall of housing. He noted, “In setting a standard for height, density, and the space between buildings, the scheme would act as a pointer to higher density development of the site to the immediate north of the appeal site and the site beyond that. All that would magnify the benefit in terms of housing delivery. On top of that, the scheme would deliver complementary, non-residential uses to serve residents and visitors, including marine related leisure, recreation, and employment opportunities. Together with the increased population the scheme would bring to the area, the vitality and viability of Brighton Marina as a whole would be improved.”

However efficient density is not everything. The Inspector noted the Local Plan policy required density appropriate to its context. The open sea was clearly crucial context. Drawings of sea stacks and cliffs did not fully convince him that a heavily urbanised, dense approach was appropriate. Historic buildings in Brighton had set a high standard as to what might be achieved, with facades such as Lewes Crescent (below) showcasing how buildings can successfully echo their context.

‘Buildings with residual spaces’ vs ‘Public spaces defined by buildings’

As the famous dual image of a vase / two faces illustrates, a design can be viewed first as buildings, or alternatively as the space between the buildings. In comparing the extant and appeal schemes, the Inspector noted the extant scheme, “is a series of buildings as objects arranged in residual space, while the proposal at issue here springs from the arrangement of spaces that are bordered by buildings. The distinction is an important one but, in my view, neither is superior to the other and either approach has the potential to work.”

The extant consent known as Wilkinson Eyre placed its design focus on landmark buildings that could be seen from a distance. In contrast, the appeal scheme put its focus on the public realm between and around the buildings as enjoyed by those using the spaces. To adapt the well known phrase, “Which comes first, the walking chicken or the tower?”

On the appeal scheme, the Inspector commented, “Given the approach that has been taken, the starting point for an analysis of the scheme appears to me to be the spaces that would be produced. For buildings of the heights proposed, some of the spaces between them would be relatively tight. That, I agree, has the potential to create interesting spaces and there are many examples of urban, and historic, places where such an approach has been successful. However, I would observe that the appeal site is not an urban (or indeed historic) setting. To the south, and the west, leaving aside the presence of the breakwater, the site is open to the sea. It does not have the built-up boundaries, or an existing network of streets and spaces to respond to, that would be found in an urban setting.…... Altogether, the various spaces want for discipline and overall, I do not consider that there are enough ‘events’ or ‘signposts’ to make for a properly legible route across the site. If spaces were the starting point for the design, then I would expect there to be much more of a pattern, or succession, to them."

He concluded: “In terms of the regularity of the façade treatments, and the homogenous mass that would be created, together with the failure to provide a proper landmark or bookend, the scheme lacks the exuberance and ambition that the best of Brighton’s seaside buildings exhibit. It would not, therefore, be a positive contributor to its context and in many respects, it would fail to take the great opportunity the appeal site presents.” On this basis he recommended the Secretary of State dismiss the appeal.

The Secretary of State’s decision

The Secretary of State considered, “the supply of housing, including the affordable provision, should, taken together, carry very significant weight.” He agreed, “the vitality and viability of Brighton Marina a whole would be improved, and that the potential for improved pedestrian and cycle access ...would make the marina a more attractive destination. ...He apportions moderate weight to those economic benefits and to the energy-efficiency of the housing (using a seawater heat pump) and improved access."

The Secretary of State could have prioritised housing delivery but chose instead to give significant weight to its design, which he considered failed to reflect the NPPF paragraphs 130 and 134 and was in conflict with the National Design Guide. The scheme’s failure to accord with the Framework, particularly the elements in paragraph 130 relating to layout, the requirement to be sympathetic to local character and history, establishing a strong sense of place and providing a high standard of amenity were afforded “significant weight” against the scheme. Overall the Secretary of State agreed with his Inspector that the design would fail to make the best of the opportunity offered up by the appeal site and afforded the resulting harms to the various designated heritage assets and to the National Park “great weight”. He gave the unacceptable living conditions for residents (with little private amenity space and some very small units) “significant weight”.

After conducting this balancing exercise, the decision rested on a knife edge but the Secretary of State had to fall one side or another. He chose beauty over delivery. Perhaps a political decision, perhaps a personal view on the design, but either way, it sets the tone for the year ahead.

Implications

We’ve all seen developments where losing a few units could result in a more attractive design. The applicant and the LPA are often engaged in a game of poker, both reluctant to reveal how close they are to either walking away from the development or refusing the application, respectively. Into such situations the amended NPPF gives a little more weight to the design side of what is often a very, very finely balanced decision.

To search for appeals of interest see our Homepage.